General

This component of the GreenX library (GX-AC) implements the analytic continuation using Padé approximants.

Analytic continuation (AC) is a popular mathematical technique used to extend the domain of a complex analytic (holomorphic) function \(f(z)\) beyond its original region of definition. For example, in many applications, a function initially defined on the imaginary axis can be analytically continued to the real axis. Such a continuation can be performed by approximating the function with a rational function, because if two analytic functions match on even a small part of their domain, they must be identical on the entire domain, according to the identity theorem. Two common choices of rational functions that are used in this context are the two-pole model and Padé approximants. Two-pole models are characterized by five parameters and their creation is straightforward but they prove to be inaccurate for approximating more complicated functions. In contrast, Padé approximants are the method of choice for approximating functions with a complicated pole structure due to their flexibility. These functions can take the form

The GX-AC component uses the Thiele reciprocal differences algorithm (A.B. George, Essentials of Padé Approximants, Elsevier 1975) to obtain the Padé parameters in a continued fraction form that is equivalent to the rational functions form above

where ${z_i}$ are a set of reference points that are used to create the Padé model. The following relation holds for every reference point:

the parameters $a_i$ are obtained by recursion:

Padé approximants are known to be numerical unstable. The GX-AC component uses two strategies to numerically stabilize the interpolation. First, it incorporates a greedy algorithm for Thiele Padé approximants that minimizes the numerical error by reordering the reference points. A validation of the greedy algorithm can be found in this reference. Additionally, it is possible to use the component with a higher internal numerical floating point precision. This helps reducing the numerical noise caused by catastrophic cancellation. Catastrophic cancellation occurs when rounding errors are amplified through the subtraction of rounded numbers, such as double-precision floating-point numbers commonly used in most programs. This is implemented using the GNU Multiple Precision (GMP) library which allows floating-point operations with customizable precision. To maximize performance, the evaluation of the Padé model uses the Wallis algorithm, which minimizes the number of divisions, an operation that is computationally expensive, especially for complex floating-point numbers and even more so for higher-precision complex numbers. Furthermore, the component also allows symmetry-constraint Padé models, for a full list of supported symmetries see the section Usage.

Benchmarks

In this benchmark section, we first analyze the effect of various parameters by using simple model functions, providing insights into their behavior, and then demonstrate practical applications in the field of ab initio electronic structure calculations. Specifically, we showcase the performance of our library for GW calculations and real-time time-dependent density functional theory (RT-TDDFT) simulations.

Model Functions

In this section we benchmark the numerical stability of the Padé interpolant of the GX-AC component using three model functions, a 2-pole model, an 8-pole model and the cosine function. A pole in the first two functions refers to a singularity of the function on the real axis of $x$, e.g. the 2-pole model has two of these singularities. In each case, a grid along the imaginary axis $z \in [0i, 1i]$ was used to determine the Padé parameters, followed by the evaluation of 1,000 function values on the real axis $z \in [0 + \eta i, 1 + \eta i]$ using the created Padé model. A small imaginary shift $\eta=0.01$ was introduced to broaden the functions, this helps avoid arbitrarily high function values or singularities in case of the pole models. The 1,000 computed points were then compared to the exact function values of the model functions to assess the mean absolute error.

Convergence with Number of Padé Parameters

The three model functions described above were tested with four different configurations of the GX-AC component:

"plain-64bit": Thiele Padé algorithm using double-precision floating-point representation."greedy-64bit": Thiele Padé with a greedy algorithm and double-precision floating-point representation."plain-128bit": Thiele Padé algorithm using quadruple-precision (128 bit) floating points (internally)."greedy-128bit": Thiele Padé with a greedy algorithm and quadruple-precision floating-point representation.

We found that the performance of “greedy-128bit” is similar to “plain-128bit”. Therefore, the fourth configuration is not reported in Fig. 2.

Figure 2 (left column) shows the real part of the exact model functions and their corresponding Padé approximants, calculated with 128 parameters, for the three different configurations. The right column of Figure 2 reports the error of the AC with respect to the number of Padé parameters. The error is defined as the residual sum between the values obtained from the Padé model and the exact analytic reference function.

Starting with the 2-pole model, the exact model is well reproduced by the Padé approximant with 128 parameters for all three AC configurations (Fig. 2(a)). The plot of the MAE (Fig. 2(b)) indicates that similar errors are achieved already with less than 10 parameters because the model is relatively simple with few features. The MAE plot also reveals that the different configurations impact the error. Compared to “plain-64bit”, the “greedy-64bit” algorithm reduces the MAE by a factor of 5 and the “plain-128bit” by roughly a factor of 10.

Continuing with the 8-pole model, the Padé approximants accurately reproduce all features (Fig. 2(c)). Since the model function has more complexity, we observe a stronger dependence on the number of Padé parameters compared to the 2-pole model. As shown in Fig. 2(d), the MAE decreases until reaching 50–60 parameters, after which it levels off. The “plain-128bit” setting again yields the lowest error.

Turning to the cosine function, the Padé approximant with 128 parameters visibly deviates from the model function for $\text{Re}(z) > 0.7$ (Fig. 2(e)). The best agreement is achieved with the “plain-128bit” setting, which is also reflected in the MAE: it is an order of magnitude smaller compared to both “plain-64bit” and “greedy-64bit”.

In general, we can conclude that the AC error is primarily determined by the number of Padé parameters and can be further reduced by using more than double precision. In some cases, improvements are achieved with the greedy algorithm without the need to increase floating-point precision.

Computational performance

Creating the Padé model (calling create_thiele_Padé()) scales quadratically with the number of Padé parameters (see left side of the figure below). The model settings influence the runtime as well. Using higher internal precision increases the computational cost and leads to a significantly longer runtime, with an increase of up to two orders of magnitude. Additionally, employing the greedy algorithm for parameter evaluation further increases the runtime compared to the plain Thiele-Padé algorithm, though this increase is limited to a factor of 3-4.

Evaluating the Padé model (calling evaluate_thiele_Padé_at()) scales linear with the number of points that are evaluated (see left side of the figure below). The type of algorithm doesn’t influence the runtime but using a higher precision internally will again increase the run time by two orders of magnitude.

Analytic Continuation in GW

The GW approach in many body perturbation theory is used for calculating electronic excitations in photoemission spectroscopy. Padé approximants are used in GW to continue analytic functions like the self-energy $\Sigma(\omega)$ or the screened coulomb interaction $W(\omega)$ from the imaginary to the real frequency axis. Both, $\Sigma$ and $W$ exhibit poles on the real frequencies axis. Similarly, as for the three model functions, we added a small broadening parameter $i\eta$ when plotting the functions in Fig. 4.

In this test, we present GW calculations using the FHI-aims package, which is an all-electron code based on numeric atom-centered orbitals (NAOs). The self-energy or the screened coulomb interaction is interpolated using Padé approximants from the GX-AC component. The G0W0 calculations are performed on top of a preceding DFT calculation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional ($G_0W_0$@PBE). We used NAO basis sets of tier 1 quality and 400 imaginary frequency points to obtain the Padé models. For comparison, we reference a G0W0@PBE calculation using the contour deformation (CD) approach. The CD technique is more accurate than AC, as it evaluates $\Sigma$ and $W$ directly on the real frequency axis. See The GW Compendium for a comparison of different frequency integration techniques.

Figure 4 shows that, regardless of the GX-AC component settings (greedy/non-greedy algorithm and floating-point precision), the self-energy and screened coulomb interaction can be accurately described using Padé approximants. For the self-energy (Fig. 4, left) the analytic continuation slightly deviates from the contour deformation because the error is dominated by the number of Padé parameters. In the case of the screened coulomb interaction (Figure 4, right) all poles are well approximated by the analytic continuation. However, the 128 bit setting performs slightly better than the double precision one when looking at the median absolute error with respect to contour deformation (0.03 eV for 64 bit; 0.02 eV for 128 bit). The analytic continuation of the screened Coulomb interaction using the greedy algorithm performs similarly to the 64 bit setting and is therefore omitted from the plot.

Analytic Continuation in RT-TDDFT

RT-TDDFT is one of the most popular and computationally efficient methods to simulate electron dynamics. RT-TDDFT relies on the propagation of the electron density in the time-domain under external perturbation. The response properties, such as the dynamic polarizability tensor $\alpha^{\text{el, RT}}(t)$, can be used to simulate the absorption and/or resonance raman spectroscopies. $\alpha^{\text{el, RT}}(t)$ is computed from the induced dipole moment as the difference between the dipole moment of the perturbed system at RT-TDDFT time step $t$ and that of the unperturbed system. A single Fourier transformation of $\alpha^{\text{el, RT}}(t)$ yields $\alpha^{\text{el, RT}}(\omega)$, from which we can compute the absorption spectrum $S(\omega)$ according to

where $c$ denotes the speed of light.

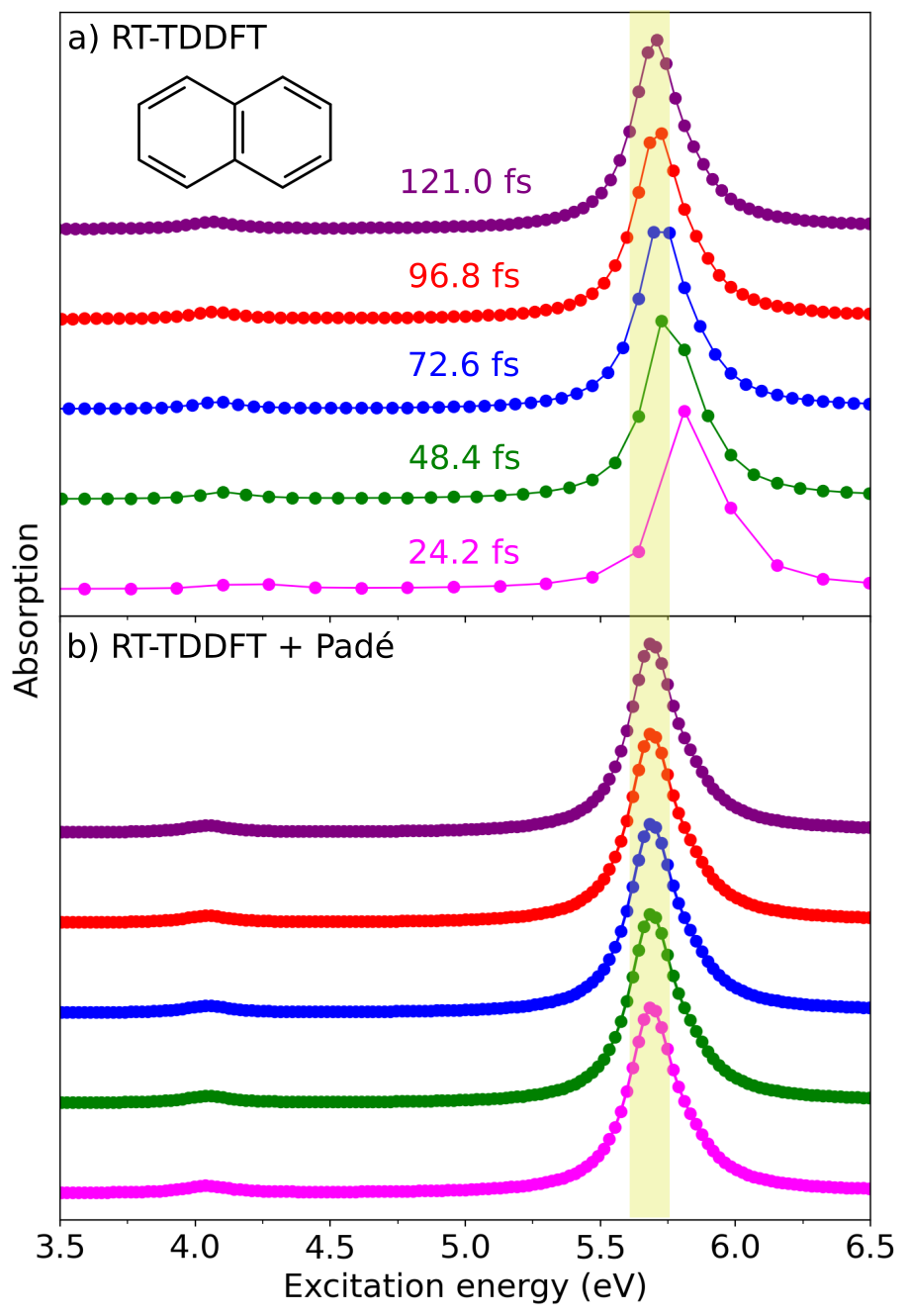

The resolution of $S(\omega)$ depends on the length of the RT-TDDFT trajectory and increases with longer simulation times, as shown in Figure 5(a). RT-TDDFT calculations are therefore computationally demanding because obtaining a converged spectrum often requires long RT-TDDFT trajectories. The use of Padé approximants enables significantly shorter simulation times and higher resolution in the frequency domain.

We demonstrate this for the naphthalene molecule. We computed the absorption spectrum computed via RT-TDDFT using the CP2K program package. We employed the PBE functional, Goedecker–Teter–Hutter pseudopotentials and TZV2P-GTH basis set. We applied the initial perturbation in the form of a $\delta$-pulse and we set the field strength parameter to 0.001 au. The RT-TDDFT time step was set to 0.00242 fs and we ran the simulation for up to 121 fs. We calculated the dipole moments of the whole simulation cell via the Berry phase approach for each RT-TDDFT step and we computed the polarizability tensors from the induced dipole moments. Using the FFTW library, we applied fast Fourier transformation to the polarizability tensors. Using the “plain-128” algorithm, we applied Padé approximants to the polarizabilities in the frequency domain.

Figure 5(a) shows the first absorption peak for naphthalene, generated from RT-TDDFT trajectories of different simulation lengths. RT-TDDFT trajectories with lengths of 121.0, 96.8, 72.6, 48.4, and 24.2 fs correspond to 50000, 40000, 30000, 20000, and 10000 RT-TDDFT steps, respectively. It is evident that, especially in the 24.2 fs trajectory, the absorption peak shifts to higher excitation energies due to insufficient data points and low resolution in the data set. The spectra seem to converge for simulation times greater than 100 fs. Figure 5(b) displays the absorption spectrum of naphthalene over the same excitation energy range, but this time with the inclusion of Padé approximants, extending the final number of data points to 80000 in each spectrum. The results indicate that thanks to the increased resolution, the use of Padé approximants allows for a converged absorption spectrum even with RT-TDDFT simulation times as short as 24.2 fs, reducing the total computation time by approximately fivefold.

Usage

There are two API functions that are needed in order to generate and evaluate a Thiele Padé interpolation. To create the Thiele Padé parameters call create_thiele_Pade() with the reference function arguments and values:

params_thiele = create_thiele_pade(n_par, x_ref, y_ref)

x_ref, y_ref must be of length n_par. After this step the parameters are stored in a fortran type called params_thiele. The parameters don’t need to be accessed. In order to use the Padé model to evaluate function values with arbitrary function arguments you can use the API function evaluate_thiele_Pade_at():

y_return = evaluate_thiele_pade_at(params_thiele, x_query)

y_return and x_query must be arrays of the same length. If the Padé model is not needed anymore, the parameters can be conveniently deallocated by:

call free_params(params_thiele)

Example of a Basic Padé Interpolation

use gx_ac, only: create_thiele_pade, evaluate_thiele_pade_at, &

free_params, params

type(params) :: params_thiele

complex(dp), dimension(:), allocatable :: x_ref

complex(dp), dimension(:), allocatable :: y_ref

complex(dp), dimension(:), allocatable :: x_query

complex(dp), dimension(:), allocatable :: y_return

integer :: n_par ! number of Padé parameters

integer :: n_fit ! number of fitting points

allocate(x_ref(n_par), y_ref(n_par))

allocate(x_query(n_fit), y_return(n_fit))

! initialize x_ref, y_ref and x_quer

! ...

! create the Padé interpolation model and store it in struct

params_thiele = create_thiele_pade(n_par, x_ref, y_ref)

! evaluate the Padé interpolation model at given x points

y_return(1:n_fit) = evaluate_thiele_pade_at(params_thiele, x_query)

! Clean-up

call free_params(params_thiele)

This is an excerpt of a stand-alone example program that can be found in greenX/GX-AnalyticContinuation/examples/. You can use this script to test the GX-AC component functionalities using a model function.

Available Options of Padé Interpolation

Fine-grained control over the generated Padé model is provided by calling create_thiele_pade()with optional keyword arguments:

params_thiele = create_thiele_pade(n_par, x_ref, y_ref, &

do_greedy = .true., &

precision = 64, &

enforce_symmetry = "none")

y_return = evaluate_thiele_pade_at(params_thiele, x_query)

The chosen options are stored in the model type and don’t have to be repeated when the model is evaluated. All possible combinations of do_greedy, precision and enforce_symmetry options are supported.

keyword argument do_greedy

Default: .true.

Possible options: .true., .false.

If true, a greedy algorithm is used to sort the reference points with the aim to lower the numerical noise. This comes at the cost of a slightly increased time to create the Padé model.

keyword argument precision

Default: 128 if linked against GMP, else: 64

Possible options: any positive number greater zero of type integer

The internal floating point precision in bit (not byte). Controls how floats are represented during creation and evaluation of the model using the GNU MP library for handling higher precision floats if a precision greater that 64 bit (double precision) is requested. The arrays containing the reference points (input) and also the evaluated function values (output) are in double precision independent of the precision keyword value. Note that a higher precision can increase the time of creating and evaluating the Padé model drastically.

keyword argument enforce_symmetry

Default: none

Possible options: See table below.

Force the Padé model to have a certain symmetry. If the symmetry of the underlying function is known, the user is advised to enforce this symmetry on the Padé model. This increases the predictive power of the model because more information about the function is provided.

| symmetry label | enforced symmetry |

|---|---|

mirror_real |

$f(z) = f(a+ib) = f(-a+ib)$ |

mirror_imag |

$f(z) = f(a+ib) = f(a-ib)$ |

mirror_both |

$f(z) = f(a+ib) = f(a-ib) = f(-a+ib) = f(-a-ib) $ |

even |

$f(z) = f(-z)$ |

odd |

$f(z) = -f(-z)$ |

conjugate |

$f(z) = \overline{f(-z)}$ |

anti-conjugate |

$f(z) = -\overline{f(-z)}$ |

none |

no symmetry enforced |

Availability of GMP at runtime

It is possible to check whether GMP is linked against GreenX at runtime:

use gx_ac, only: arbitrary_precision_available, create_thiele_pade

if (arbitrary_precision_available) then

! this will succeed

params_thiele = create_thiele_pade(n_par, x_ref, y_ref, do_greedy=.false., precision=320)

else if (.not. arbitrary_precision_available) then

! this will result in an error

params_thiele = create_thiele_pade(n_par, x_ref, y_ref, do_greedy=.false., precision=320)

end if